Coming in an email to me this week were some questions which the writer wanted me to answer. She was interested in what I would say to c-suite execs. She asked:

- How is the pandemic affecting how organisations should be designed?

- What advice would you give to enlightened organisations on how to improve organisation design?

- How important is company culture in all of this?

- Can you give a real-world example of a company getting it right? Any lessons other could use from this case study?

- Is there any other advice you would give execs about helping to create an organisation and a workforce that will emerge even stronger once the pandemic ebbs away? And what are the biggest challenges?

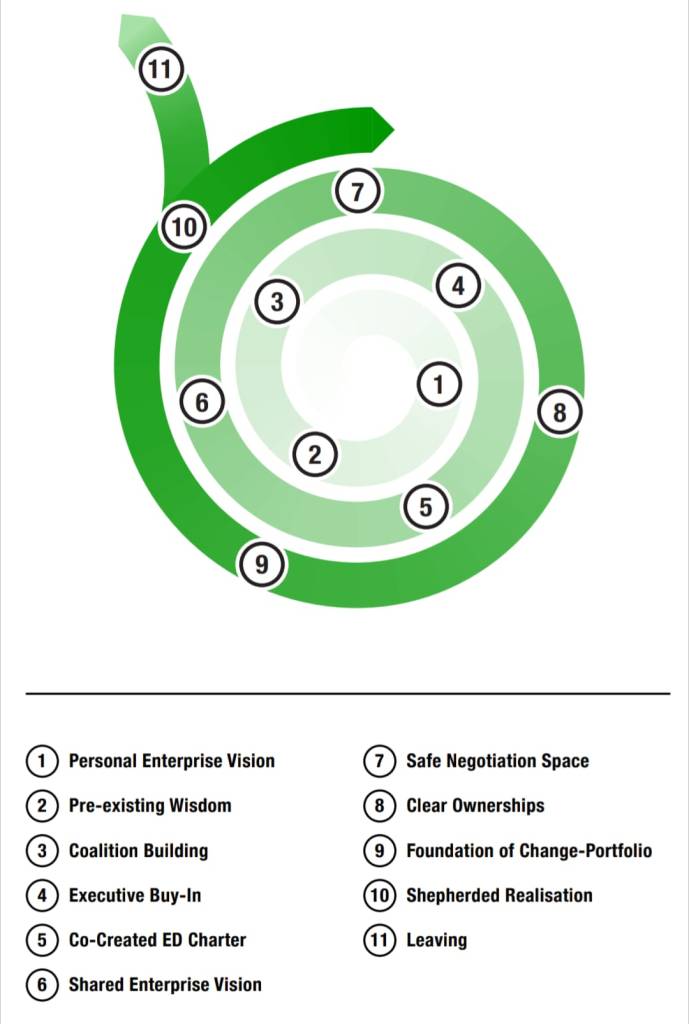

The thing was that she wanted a total of 250 words in response. Having just written a whole book (around 100k words) that aims to answer these questions, I was reminded of my long-ago manager’s request that when I was presenting my PhD research to the exec team, who had sponsored it, that I reduce the thesis to a one-page graphic.

However, I did manage to reduce my thesis to a one-page graphic so, undaunted, I will have a go at summarising the book/answering the questions. (The book is coming out on 13 January and is available on pre-order, Designing Organisations, why it matters and ways to do it well.)

My final para this week is on my decision to press pause on this blog.

…………………

Organisation design in pandemic times

Since 23 March 2020 (when the UK went into the first of the pandemic response lockdowns), it’s become clearer that exec teams who:

- are prepared to challenge their assumptions on their strategy, business model and operating model. (See my blog Future Operating Models)

- keep a clear mind on what aspects of their business remain stable and what can be rapidly changed (See my blog Designing Resilience)

- have good data – both quantitative and qualitative – on which to make decisions (See my blog on Data and Complexity)

have been more likely to demonstrate the resilience needed to weather the on-going effects of the pandemic. Leaders of pandemic resilient organisations have made bold decisions – shifting their business strategy, adjusting their business and operating models and continuously adjusting aspects of their organisation design, including systems, policies, and authorities.

The stories of two UK retailers, John Lewis and Next provide good examples in their sector of design responses. ‘Clothing retailer Next has grown by developing its in-house brands, expanding overseas and opening up its website, warehouses and delivery services to brands that struggled on their own’, while John Lewis has closed stores, grown its online sales from 40 per cent pre-pandemic to 75 per cent by October 2021. By 2030, Sharon White, John Lewis’s chair, wants the organisation to take 40 per cent of its profits from new areas and is considering offering homes, financial and wraparound services.

It’s too early to say whether these two organisations will be successful over the next decade, but compared with retailers Debenhams, Topshop and House of Fraser, who have collapsed, both John Lewis and Next, are indicating ways that they are changing their designs as a pandemic response. They both have executive teams with the attributes mentioned earlier (to challenge assumptions, keep a clear mind, draw on good data). These attributes enable executives to pick up on adjacent possibilities, take some calculated risks (after testing and consultations), and move swiftly.

There are many examples of organisations in other sectors demonstrating this same basket of attributes and actions, who are doing well in redesigning their organisations – Shopify, Netflix, Zoom, Paypal, Peloton, Wayfair – but their ability to capitalise on these depends, to some extent on the processes, policies, technologies and cultures that were in place at the start of the pandemic. The RSA offers a useful Future Change Framework for organisations to reflect on their design responses to the pandemic, giving some ideas on how they might continue to adapt. (See blog image).

Turning to cultures – usually there are many cultures in a single organisation – they change as broader societal norms change. As well as the pandemic, the last couple of years have seen accelerating conversations and actions around race and ethnicity, mental health and well-being, gender, labour movements, conditions of employment, sustainability, environmental issues, and so on. All of these have an impact on an organisation’s design. As much as the pandemic these issues have contributed, and continue to contribute to organisational redesigns. Alertness to societal trends and pre-occupations, noticing how these are reported, disseminated and talked about and to have considered conversations on how, when, or if, to respond should be high on every executives’ agenda.

Thinking the pandemic will ebb away, is probably a mistake, because it conjures up an image of a more stable and tranquil context than that we have been experiencing. The pandemic may continue and/or may be replaced or supplemented by different turbulences – we are already seeing rare metals shortages, supply chain vulnerabilities, geo-political tensions, bio-diversity loss. And we are simultaneously seeing massive strides in quantum computing, bio/health sciences, AI and robotics, etc. Probably the biggest challenge for organisation designers/executive teams is to differentiate the signal from the noise (see a review of Nate Silver’s book on the topic), and to make sound judgements on which to respond to (and why).

[Ed: you failed on 250 words. This is 650]

……………….

Pressing pause

This is my #862 blog on organisation design. My first was posted on 23 September 2008. I have decided that this is my last one for now. I am pressing pause. I do not know if or when I will return to this blog but I will leave it open and available for people to browse. Someone asked me why I am not continuing to the nine hundredth one, and I considered that idea but have still opted for new year, fresh start.

My thanks to all those readers, commentators, friends, colleagues, and random strangers who have, over the years, triggered some thought that has turned into a post. I’ve found the writing process wonderful – a continuous learning, thinking, and researching on a topic I am passionate about. I will continue writing with the same enjoyment and discipline that this blog has offered – but as I explore new directions, I’m guessing new writings will emerge from them. All the best for 2022. May your cup always be full.

You must be logged in to post a comment.